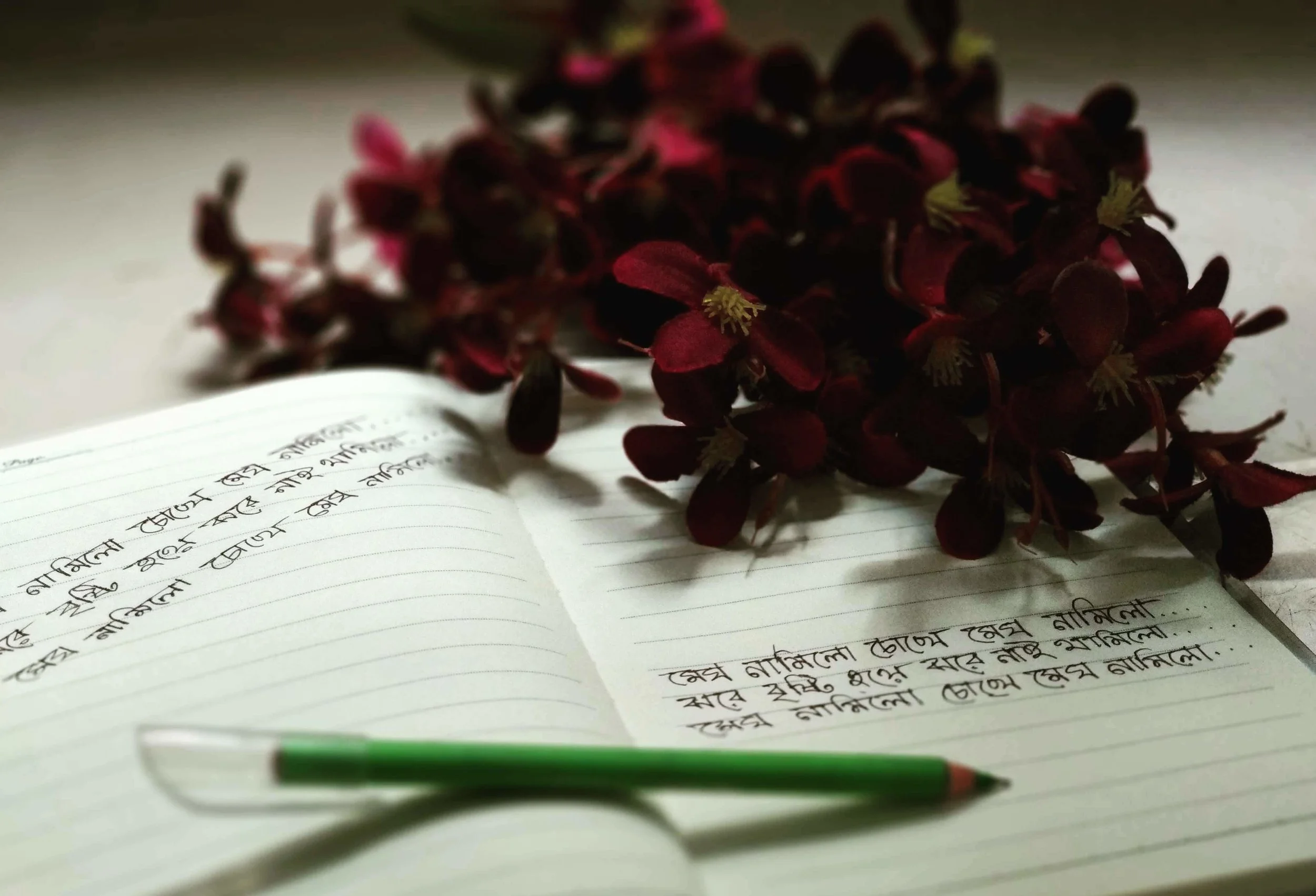

Growing up as a Bangladeshi, there is one thing that my parents always reminded me: you are from a country where people died for their right to speak their language.

Some people might know that International Mother Language Day is on the 21st of February, and it’s to celebrate and honour our mother languages. But Bengalis know the day as Ekushey February, the day we commemorate those who died for us to be able to speak our mother language. It’s not simply a day of celebration, but a time to honour the language that our predecessors fought and died for.

There is a lot of responsibility that comes with being a Bengali writer. My Dad always reminds me that, though I am writing in English, I should never forget my mother language is Bangla. As someone in the diaspora whose grasp of Bangla comes from studying the language in school until I was ten years old, and now only speaking it to my parents and relatives in the language, it’s a difficult thing to balance. How do we write in English and still portray our mother language? How do we share our stories with the world and still honour the language of our people?

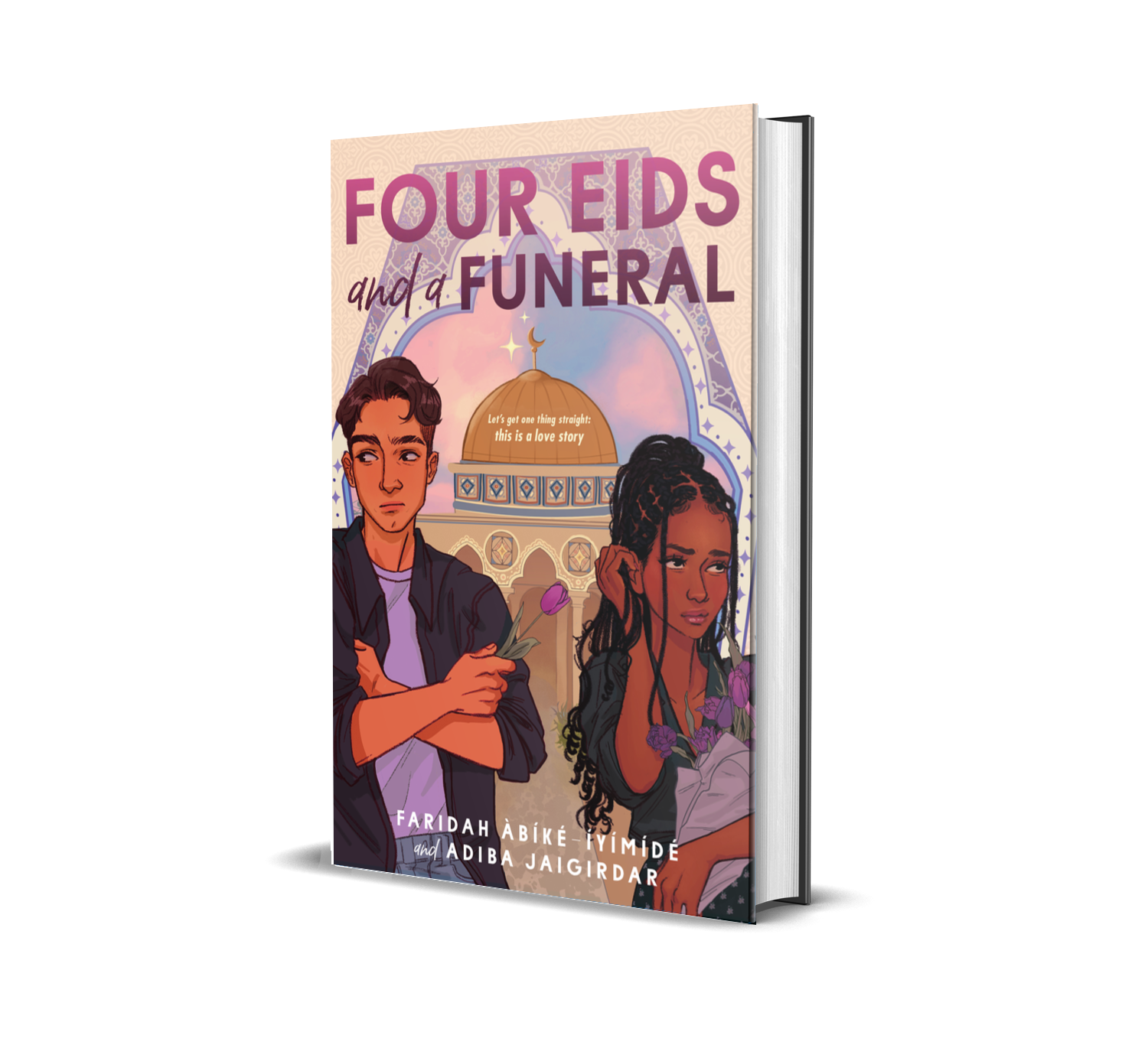

Writing a book is no easy feat, but when I first sat down to write a book with a Bangladeshi character, I found myself up against an unprecedented challenge: I had never read a Bangladeshi character in a book before. I hadn’t seen a Bangladeshi character on a TV show, or in a film. Though I had grown up with, and surrounded by, Bangladeshi people, I had no idea how to tell a story about people like us. So as I sat down to write, it wasn’t the idea of writing a novel that was daunting, it was the challenge of doing something that I had never seen done before: writing about someone like me.

Writing as a person of colour often means writing with no blueprints set out in front of you. It means navigating new territories in writing. Navigating the responsibility—and burden—of representing not just yourself, but everyone who shares your culture, religion, language, ethnicity. Along with this, comes the difficulty of navigating a new linguistic landscape.

In my everyday life, I speak in different languages. With my parents, and most of my older relatives, I speak in Bengali. With my siblings, and Western cousins, I speak in “Bang-lish,” which is essentially a mixture of Bengali and English. With non-Bengali people, I mostly speak in English

As I began writing a book with a Bangladeshi and Irish immigrant character who went through life with a similar linguistic experience as me, I had to ask myself how do I translate my real-life experience with language and expression into a book form? How do I do it, while still being true to my lived experience, and engaging to an audience that doesn’t necessarily share the same experience?

Firstly, I tried it exactly how I had learned non-English languages should be presented in books: I italicised everything that wasn’t English. I wrote footnote explanations or direct explanations right there on the page. I essentially circled every non-English word in my writing with a red pen and screamed, “here’s something different!” It was as unauthentic as I could make it. After all, when I think in a jumble of Bengali and English, when I speak to my family in Bang-lish, there are no italics to mark the difference between that and the English many of my peers speak. There’s my experience of language and their experience of it: different, but both as valid as each other.

After this failed experiment, I had an idea of exactly how I wanted to write my story: with me at the center of it. That is to say, without stripping back language or experience for someone who was not experienced in my language or my culture. I wanted to write characters who lived authentically in my story because they did not have to cater to someone with little to no knowledge of their language and culture.

At the time, I thought it was impossible to do this and still have some hope of being published. After all, for most of my life I had read books that did mark out languages and cultures that were “different.” Books that seemed to speak to the people living outside of the characters’ lived experience, rather than to those inside it.

Thankfully, I read two books that changed my mind. The first was When Dimple Met Rishi by Sandhya Menon. In the pages of this book, Menon had written out entire conversations in Hindi between her main characters and their parents. The second, Love From A To Z by S. K. Ali, where Ali includes Arabic script as one of the main characters—Zayneb, who is Pakistani, American, and Muslim—writes in Arabic inside her journal. These books are obviously far more than these small instances. But it was these small instances that emboldened me to write my stories, and my characters, as fully as they deserve to be written. Without the hindrance of a second gaze peering over my shoulder.

Growing up as a Bangladeshi, we are often hyper-aware of the history of our language. Every mother language day, as we celebrate our mother tongue and mourn the martyrs of the language movement, we remember the importance of our language. To speak a language with this history is a gift, but as an immigrant coming to terms with identity, and as a writer coming to terms with identity in the form of stories, it can be a heavy weight to bear. I can only hope that I’ve done my best to honour it in my work.