Welcome to Muslim Voices Rise Up, a month-long project taking place during Ramadan where Muslim authors and bloggers share their experiences on various topics! This project is dedicated to centering Muslim experiences and showcasing the diversity within our own narratives. You can find more info, along with other blog posts for this project, on the introduction post. In today’s post, some Muslim folks in our community share the importance of #Ownvoices Muslim stories:

Farah Naz Rishi

The first time I’d ever seen Muslim characters portrayed in a book—written by a Muslim author—was Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner, written in 2003.

I was thirteen years old.

Consider that for a moment: I had never seen a character in any form of media who’d shared my faith until I was thirteen years old. An entire childhood without ever seeing another person on the page that prayed the way I prayed, or fasted during Ramadan each year (or tried to, at least), or celebrated the same traditions I did. I’d never seen another character say “asalaamualaikum” to another, or frantically whisper ayat al-kursi when they were frightened.

For thirteen years, I had never seen anyone even remotely like me beyond the walls of the mosque, my home—or within my own mirror.

Sure, beyond being Muslim, I didn’t really have much else in common with Amir, the protagonist of The Kite Runner: for example, I’m only about a quarter Pashtun, and I identify as a woman; I’ve never been to Afghanistan, and although I know how to fly a kite, I have no idea how to “kite fight.”

But that one similarity—our shared faith—meant everything to me, especially when I was first navigating the post 9/11 political and social landscape.

Islam had never really been at the forefront of my mind, prior to 9/11; as a middle schooler, my only focus had been on trying to survive the notoriously awkward preteen phase of zits and unibrows and one-sided crushes. But when 9/11 happened, my Muslim identity suddenly transformed into an unignorable red target on my back. I could no longer treat my religion as a single facet of my identity, a single color in a kaleidoscope of the Self, as most children could. To the rest of the world, I was now an emissary for my religion, and in a school where I was one of the only people of color, and the only Muslim, I was my religion, whether I liked it or not.

When the usual questions directed at me (You’re Muslim? Does that mean you worship cows or something?) began to sound more and more like loosely-veiled threats (Is your dad Osama bin Laden? Where are you hiding your bombs?), reading a book with a Muslim protagonist was a simple, yet impossibly powerful reminder, one the author had meant for me: that I was not alone, despite the world persistently trying to convince me otherwise, and that I too, despite everything, could be the hero of my own story.

Sixteen years later, every book I’ve read with a Muslim protagonist has served to make that message stronger, to embed that feeling of unseen unity, in a heart that would otherwise feel hopelessly abandoned in a country I called home. Without those stories, it would have been so much harder to shut out the whispers that called my family villains and monsters. Without those stories, I wouldn’t have the confidence to pick up a pen. That is the power of reading books written by authors who share your identity: only they can navigate through the dark labyrinth of doubts inside your head to reach you. It is, after all, a labyrinth they know all too well.

The #OwnVoices movement (as coined by writer Corinne Duyvis) is so much more than a hashtag. It’s about encouraging authenticity in the books we read, and ensuring those books reflect the real, diverse world we live in. It’s about boosting those marginalized voices who, at best, are made to feel small, and, at worse, are often silenced by the din of privilege. It’s about acknowledging the simple fact that no one can tell the stories of marginalized people better than us.

Part of being an effective writer is to come to terms with the fact that even with all the talent in the world, or an arsenal of all the research in the world, you might not be the right voice for that story. And that’s okay. If writers have a duty to deliver the best possible story to their readers, the reality is that not sharing the identity of the character you are writing will put you at a severe disadvantage. Authenticity means little without the backing of lived experience.

And honestly? Any less wouldn’t have reached that lonely thirteen year old girl.

Author of upcoming I Hope You Get This Message.

Twitter: @far_ah_way

Website: farahnazrishi.com

Maria Hossain

A few days before I wrote up my section of this topic, I was reading a political fantasy book by a white woman. She is also non-Muslim. When I found several Muslim characters from the Ottoman empire, I was curious. Soon I discovered one of the protagonists is Islamophobic. The protagonist subsequently falls for a Muslim man and their sibling also converts to Islam. But one wording in their letter to someone still sours my mind.

The wording is "the plague of Islam.”

I think, after all this time, non-Muslim people still view Muslims as a monolith. Whenever they think of any Muslim person, they visualize hijabi woman, niqabi woman, man in skullcaps and robes, and how men are depriving women of their rights by subjugating them. Whenever the non-Muslim folks think of us, they think we are all the same. We all do the same things, and think and speak the same things.

Which brings me to this topic. Why #ownvoices Muslim stories are important. Because whenever non-Muslim people think of us, they associate us with Middle Eastern, especially Saudi Arabian, cultures, when the truth is, 62% Muslims in this world are from Asia-Pacific regions. Islam is the second largest religious tradition in this world. How can people from a religion so widespread be a monolith? That's obviously impossible.

And yet most non-Muslim people think of us that way.

This is why we need more #ownvoices Muslim stories, from every single culture Muslim people are from. So others can see, we are NOT a monolith. We are as diverse as people from any religion or country. We have Muslims all over Asia (and I mean all over, even in East and North Asia), Africa, North America, every single continent. And we are not monolithic. We are diverse, we are just like you.

This is why, I think #ownvoices Muslim stories are more needed than ever before.

Twitter: @maria_writes

Blog: Maria Hossain

Farhina

What do I mean by "ownvoices?" Here, When I say the term “ownvoices” I am referring towards the phenomenon of being “represented” in media - seeing or reading about characters like one’s own self in books, TV, movies, etc. It means to have a source, medium, a character you could relate to, find solace in their existence. Representation pertains to many different aspects of identity. It can be about your culture, body type, race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, disability, class, age, and even issues/life circumstances, etc.

#Ownvoices books gives people a chance to be uplifted. See their circumstances being told, to be able to relate. As a human being we all strive to have a connection, to get that strand of hope that we aren’t alone in the world, that we matter and there are people like me around.

Representation, and why it matters? Growing up with characters that weren’t like me wasn’t a huge deal to me, as it is to most people. Up until last year I wasn’t into the whole I need representation deal personally. And hadn’t read most of the ownvoices Muslim books, because almost all of them are about romance or rebelling against religion and I couldn’t relate to that. But then I read City of Brass, and everything changed, I can’t tell you the joy I got from seeing myself, or somebody like me being there doing the things I would. Seeing the culture I could relate to. I can’t explain the feelings but it was delirious and amazing. And I understood in those numb feeling of being left gob smacked why everyone was going on and on about the importance of representation. And everything changed.

Yes, we need voices like us in our stories, to be able to relate, for that kid to see a brown super woman that looks like her, to grow up on stories. And to get that self believe that yes even she can soar and touch the sky.

Here is a quote I got from fellow Muslim reader @hamad and why own voices Muslim books mattered to him, to get another voice into the mix:

" When I started reading in 2015, I didn't notice diversity and representation and this stuff. I then as the time went on started to notice that the characters kind of fall into the same mold and that kind of made them flat, unrealistic and boring for me. I wanted to see myself in a book, I wanted to see more Muslims, more black people, more Arabs, more of everything other the typical YA character. I remember reading about a character of color in the shatter me series, his name was Kenji. He was so unique, the author is a Muslim and that made me appreciate the character even more! I started to look for more characters like him and found out that I have learned many things about different cultures and different people in the community. After the New zeland attack, I was kind of attacked on the internet because I am a Muslim and that's when I decided to host a Muslim readathon to expose others to more genuine representation that that in the media. Simply put: representation matters!”

Diversity is all around us, whether we like it or not. Your black neighbor, your Muslim best friend, your disabled cousin. They need to see themselves in books. And we need to see them to know that this is normal. Too see their stories, see life from their point of view and to learn from their experiences. Ownvoices books can be a huge and an important deal in bringing acceptance, tolerance and understanding of all the marginalized, understated and misunderstood communities.

Naima from @nerdsforbooks says:

“I’ve read many books which make me happy but the inexpressible joy that I get whenever I come across a Muslim character is something else entirely It’s an amazing feeling to be represented, to know there are people out there like me, and to know that people of other cultures are reading about us and maybe understand a little about us, other than just hearsay.”

In current day and time people can be so easily misinterpreted and voiced in stories in a way that they aren’t, and can have hostile environments created for them. Muslim representation matters because the media can trick people into false stereotypes. Many people think of Muslims as the Stone Age man, who is a terrorist now. That’s why Muslim stories need to be told. When they see Muslims in books. When they see us as their equals. Too see that we aren’t the barbarians the media portrays us to be. How we belong to the most peace loving religion. How the percentage of the world of people with messed up ideologies don’t represent us. How we are the same as them, with similar struggles that they would 100% relate with. How they see you, changes the society hopefully toward the better more accepting tomorrow.

Twitter: @shelovestoreaad

Blog: She Loves To Reaad

Instagram: @shelovestoread

Raghaad and Zahra

As Muslim girls growing up in the Middle East, we have been exposed to Western media ever since we were kids, whether it was books, TV shows or movies. But we never really felt connected to the stories we were consuming, the lavish life in LA, the busy rush of the big apple, or the tall gorgeous white girls who have their lives together just felt like something literally out of a movie, because they were. The media you consume, especially when you’re younger, really affects the way you think and look at life. For a while, it was not evident that the lack of representation was important as we could see people like us on the street and in our local communities. But after a while and as we grew a little older, seeing these girls who look nothing like us on a TV screen or in the words of a book, being successful and living a great life with no problems made us feel like we’re missing something, we felt jealous over things we couldn’t control, like the shade of our skin or the color of our eyes.

Raghad recalls 6th grade when they had an assignment to write a short story about anything they wanted. She first started writing about an Aisha that went to school like us, but couldn’t finish it because all the books that inspired her to write were based on girls that didn’t look or speak like us. She ended up changing the whole story to one that was filled with white characters that were not Muslim. This theme continued in our reading life and it started giving us a sense of detachment, like the world we are living in and the world we read about were two different things.

Yet as we grew older, and as the internet started making all of us more connected than anyone would ever imagine, we started to learned that the west has Muslims just like the Middle East has Christians, and yet we never saw a hijabi on a TV show until 2015 when Quantico first came out. It was a shock followed by pleasant surprise as we saw someone that resembled us in a normal setting doing whatever it is TV show characters did. And when we both first read our first books with Arab Muslim main characters, it was a life changing experience. We found ourselves laughing out loud and relating to the most mundane parts of a story, which is something that makes you appreciate and love a story even more than main plot points and character traits.

As time passed and we learned more about just how diverse the world is, we realized that the dominant media is not as diverse as the world really is. Even after we started to see Muslim and Arab representation in the media we consume, they still felt like strangers. They were not people we saw ourselves in, because they were not created by the people they were representing. When a story is not “own voices”, many misconceptions infiltrate the core of the story and a lot of mainstream ideologies get plastered all over the characters. The characters are also usually so westernized in order to “fit in” that they no longer represent what it is to be a Muslim or an Arab, which was mostly either a terrorist, lavishly rich, or someone trying to cut loose the strangling ties of Islam. We found this bewildering because just like we see a small fraction of what the west is like, they also see a very small fraction of what the Arab world is like, because they have not shared our history or lived our life.

Not everyone can become a writer and write their own story in order to find some content that they feel that they can relate to, and this is why “own voices” stories play a huge role in media. You always write best when you’re drawing inspiration from the world around you, the experiences you lived through, and your own life. It is the best way to keep it real and simple and accurate, and someone who has never even seen what an Arab or a Muslim household is like, can never give the correct adaption on a screen or on paper. We as Muslims and all the other minority groups should also have our chance to deliver to the world our stories and our culture. We need to help the next generation of minorities find themselves in books and TV, because our voice and stories matter.

Twitter: @LeBeard13 & @RaghadMHD

Instagram: @thebookishzebras

Azrah

When books are your go to escape they mean so much more when they involve characters that you can relate to and #OwnVoices books have taken this to a whole new level.

The sheer ability to walk into a bookshop or library nowadays and to find a book centering on a Muslim character or solely a book written by a Muslim author is inspiring. From those that I have read, simply stumbling across subtle references to our beautiful religion in a narrative or coming across phrases or gestures that are familiar to my own culture fills me with joy. More so that we can share this with others, especially in a world where are our faith is still, quite too often, misunderstood.

My love for #OwnVoices books overall, stems from the teaching element that they provide. The fact that we have these books to allow us to learn about and embrace different cultures and backgrounds is wonderful and so so important!!

A question that was often thrown my way when I was younger, both out of ignorance and curiosity was “how can you be Muslim when you don’t even cover your head?” In more recent times I have had people, albeit indirectly, belittling the extent of my faith simply because I don’t seem like the type who truly practices.

Muslim stories when written by those in the position to tell them can help to break these misconceptions and stereotypes that the world cannot be without. Help us to look beyond the conventional opinions and prejudices that are still very prominent within our religion today. They are a step towards allowing those on the outside to gain a wider understanding of our religion and providing those of us on the inside the opportunity to reflect upon ourselves and our fellow Ummah (Muslim community).

Everyone has their unique story, a unique relationship with their faith and the #OwnVoices movement has provided a platform where Muslim’s from all walks of life are able to share theirs.

I’m always thinking how amazing it would have been for these stories to have been there for me to read whilst growing up so I’m just immensely grateful that they are starting to become more available now.

Twitter: @rahrahremus

Blog: Quintessentially Bookish Blog

Vianna Goodwin

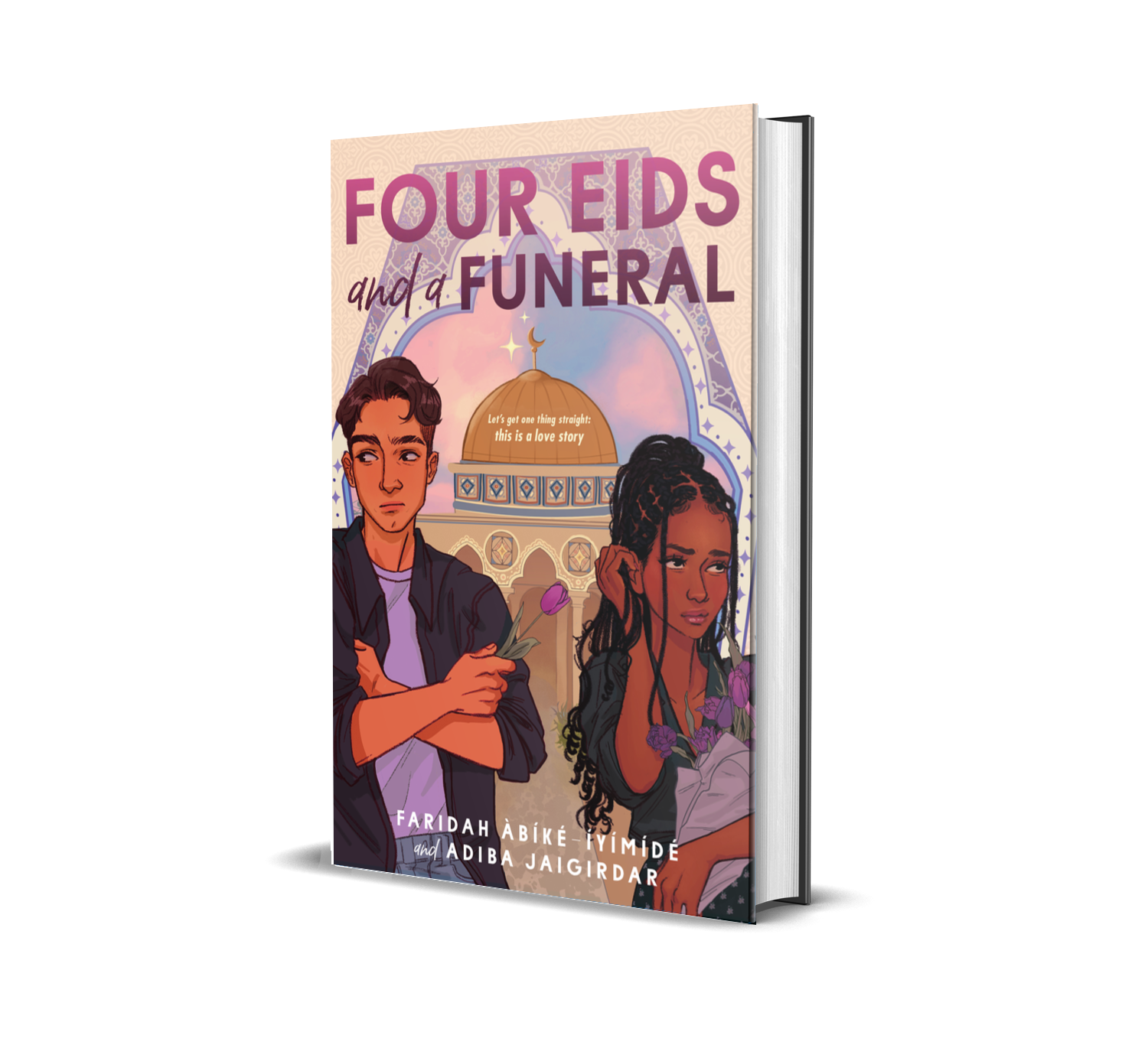

This year has been an exciting year for Muslim authors releasing their ownvoices stories. It wasn’t until I got my hands on the first of many releases that I realized just how much I’d been missing seeing myself in characters that weren’t just there to further another character’s mission. Muslims are rarely represented in fiction unless they fall into a few stereotypes. It’s frustrating to see the culture that I love so dearly reduced to a handful of roles to drive the story along. Need a bad guy? Let’s make that guy a terrorist. Need a woman triumphing over evil? Let’s make her defy Islam, embrace “freedom” and turn away from her family. And then there’s the fact that nearly all Muslims portrayed in these stories are Arab by default. There is so much ignorance about Muslims and our diversity, and the ugly roles we are often given in stories is disheartening. Yes, there are bad people in every culture, but there has never been anything to balance the scales in our favor. This is one of the biggest reasons I set out to write my own books, but along the way, I found that there is a surge of ownvoices stories being released, and it’s beautiful.

Being able to read a story with elements that are uniquely Muslim is such a delight, and it makes me feel seen like nothing else can. We’re so used to everything being written under the white (and typically Christian) gaze that every little bit jumps out at me. The girls altering their steps, trying to have their right foot cross the threshold first while they giggle. The stories with djinn being treated as casually as other stories talk about angels and spirits. The diversity among us, and the familiar words that aren’t translated so non-Muslims know what they mean. There is something so uplifting about a book that gets us; a story that is unapologetically Muslim. And these stories are not just for us. They show others that we have lives that don’t have to center around our pain and discrimination. Muslims are “normal” people with problems like everyone else, and it’s so refreshing to see our realities reflected in ownvoices stories.

But it isn’t just this generation that benefits. Our younger generation deserves to grow up seeing themselves in books. And not just the girls that stand up for themselves and choose not to cover because they feel liberated. These stories are valid, too, but so many books with Muslim women and girls focus on shunning the practice of hijab. We need girls that embrace the hijab because that’s how they resist western oppression. In this modern world, resistance comes in many different forms and it’s time we celebrated that. We need characters that embrace Islam with honesty, humility, and a bit of humor. We need women and girls who wear hijab despite the dangers they may face, showing their strength and the fortitude that so many of our women have. And we need characters that are having adventures like all the other characters in millions of books without having to make a political statement. There is so much about our various cultures we haven’t explored, and I cannot wait for the years to come. The industry is changing and it’s beautiful to see. Yes, there are still problematic stories that crop up, but as people are educated and Muslim voices are boosted, we’re making sure these issues are addressed so that harmful stereotypes aren’t perpetuated.

As a Muslim woman who has experienced prejudice, hatred, and fear simply for the cloth on my head, ownvoices means that I’m not alone. And with each new book, I am building a sizable library of Muslim-positive stories for my own daughter. My dream is that she will have more books celebrating the Ummah without catering to western understanding. I’m doing my part to make that a reality, but I wouldn’t be on this journey without the trailblazing women who came before me. Seeing ownvoices books in print has inspired me like nothing ever has. I’m hopeful for the future of literature, and I’m grateful to be a part of this beautiful community of Muslim writers and readers. We’re changing the world one book at a time. Alhamdullilah.

Twitter: @GoodwinVianna

Naheed

Growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area in the seventies, my sister and I were the only Muslim kids at our school. No one really knew what a Muslim was and we spent most of our time explaining we were Indians from India, not Indians as in Native American Indians. It wasn’t till I was eleven when I first met a Muslim character within the pages of a book. It was written by Louis Fitzhugh, the author of Harriet the Spy. In Sport, I finally found a character, Harry, who somewhat resembled me. A Black Muslim kid, he was proud of who he was, an integral part of the kaleidoscope of multicultural New York City.

It wasn’t till 1989 that I found another Muslim in a book when Shabanu: Daughter of the Wind showed up at the library. Within its pages, I was transported to Pakistan to meet twelve-year old Shabanu, the daughter of a camel herder in the Cholistan desert, forced to marry an old man to settle a family dispute. Although the novel raised legitimate issues of child marriage and patriarchal practices, it was written in a way that portrayed Pakistani Muslim women as exotic, culturally backward and oppressed - it exacerbated negative stereotypes and left me feeling ashamed that this represented my culture and religion. The book went on to win the Newberry Award, the highest honor in children’s literature. It also went on to become a commonly read text in schools.

I didn’t encounter any more Muslim characters for years, but I continued to read, always amazed how books could magically provide a window into new worlds. I loved meeting characters I wouldn’t have run into in my community or neighborhood. When I was ten, I wanted this magical talent myself – to use words to create my own stories By the time I was an adult, I felt that the need to create stories that were from my own culture and background that would not only serve as windows, but also mirrors. Mirror books allow children to see themselves, their culture and community accurately represented in books, helping to promote positive self-esteem. Books that serve as “windows,” provide children a glimpse into the diversity of the world in which they live, helping them develop respect for unfamiliar people, places and lifestyles.

My inspiration for my first book came from my husband, whose family escaped Afghanistan when the Soviet Union invaded 1979, and immigrated to the United States. Thus Shooting Kabul was born. As I plotted out the main character, Fadi’s journey, I knew my overarching goal, as with all writers, was to write best story I could, one that kept readers glued to their seat. However, I felt a great responsibility to convey a story about Muslims, Islam, Afghan culture and the events of 9/11 and terrorism in a nuanced way – creating a story that served as both a ‘mirror’ and ‘window’ for my readers.

Since Shooting Kabul debuted, nearly a decade ago, I’ve received countless emails and letters from kids across the country. Muslim readers found a mirror in Fadi’s story and expressed their heartfelt thanks at meeting a character like themselves. Non-Muslim children conveyed their appreciation for gaining insight into the lives of Muslims in America and around the world, by peering through a window into Fadi’s world.

With the presidential victory of Donald Trump, who built his platform on xenophobia, racism, misogyny and Islamophobia, the current environment for Muslims has become even tougher. Now, more than ever, we need to build bridges of understanding between all Americans, and I feel that literature provides a platform for children to connect with others. Hopefully, reading across racial, cultural and religious divides, kids can be emboldened to reach out to classmates different than themselves, which is especially important as we see the rise of bullying and animosity towards Muslim kids (and those who appear Muslim) I truly believe that young people have the ability to be agents of positive change for the future.

Author of Escape From Aleppo

Twitter: @NHasnatSenzai

Website: www.nhsenzai.com